College of Marin trustees have agreed to further explore participating in a program to guarantee rental income at the Oak Hill workforce housing project in Larkspur.

The college board unanimously endorsed a resolution Tuesday directing staff to do additional analysis on whether the move would be a valuable long-term investment.

“We know we’re not signing up to guarantee the program at this moment,” trustee Stephanie O’Brien said. “But to me, it would be unconscionable to not continue this due diligence and to move forward.”

The vote makes the college the fourth public entity to agree to consider the guarantor program. Five agencies are needed to fully guarantee the project. Others on board or conducting due diligence are the Novato Unified School District, the Marin County Office of Education and the county.

San Rafael City Schools, the fifth potential participant, is scheduled to hear a presentation on Monday.

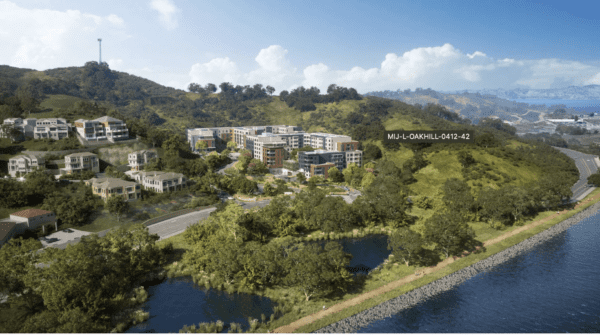

The guarantor program is needed to help close a $16.4 million budget shortfall in the 135-apartment, $118 million project, said Matthew Hymel, executive director of the Marin County Public Financing Authority. The proposed complex would be built on 8 acres near San Quentin prison.

The shortfall stems from rising interest rates over the last couple of years, according to Hymel, a former county executive. The authority, which was created in 2023 to oversee and administer the housing project, is a joint agency of the county and the Marin County Office of Education.

Full participation in the guarantor program would reduce the interest rate on Oak Hill’s construction bond, potentially allowing for $400 less in monthly rent per for each apartment for a year, Hymel said.

The apartments would be rented to school employees and other public workers earning between 50% and 80% of the area median income. For example, a household of three earning $88,150 per year in Marin is at 50% of area median income, while a household of three earning $141,000 a year is at 80%.

Of the 135 apartments, 101 would be reserved for Marin public education staff members, and 34 for county employees.

Each of the five entities would guarantee rental income for a set of apartments over a 40-year term. So far, the Novato school district is considering 27 apartments; the Marin County Office of Education is planning for 20 apartments for employees at smaller school districts; the college is considering up to 18 apartments; and the county is considering reserving 34.

If the vacancy rate for a particular group rises above 4%, the public entity for that set would be responsible for the missed rental income. However, Hymel said that a recent housing demand survey indicates that at least 300 people annually would be interested in living at Oak Hill, especially if the rents are kept affordable.

The public entities also would have access to various housing waiting lists that could be used to fill any vacancies if necessary, Hymel said.

On Tuesday, both the college board and Marin County Board of Education trustees heard from more than a dozen program supporters, as well as critics, at separate meetings.

“At the end of the day, the benefits outweigh the risk,” Jenny Silva, executive director of the Marin Environmental Housing Collaborative, said at the county board meeting.

She was referring to the increasing difficulties Marin school districts have in recruiting and retaining teachers because of the lack of affordable housing.

“This project could have people living in it as soon as two years,” Silva said.

Chandra Alexandre, chief executive of Community Action Marin, a social services provider, said Oak Hill is a “generational opportunity for workforce housing” that would be “an essential foundation” for the community.

“There’s no plan B,” said Alexandre, who spoke at the county meeting. “This is a real opportunity and there are no others in the pipeline.”

Mimi Willard, president of the Coalition of Sensible Taxpayers, said she has requested a list of all the financials for Oak Hill, but was told the numbers could not be released. She told College of Marin trustees that should be a warning.

“You are being encouraged to make what I think is a monumental decision based on what’s largely a fact-free presentation,” Willard said. “Essentially, you’re being given some numbers about supposed rental demand, not what the prices are likely to be, what the operating costs are likely to be, what the interest rates are likely to be.”

Stephanie Andre, a Larkspur City Council member, said the college should take a lesson from the problems with Serenity, an affordable housing project in Larkspur that is now in default.

“You should absolutely ask for pro forma financial statements in a full capitalization structure before you proceed,” Andre told the college board. “Proceed with caution. There is risk here with real estate investments, and what we’ve seen at Serenity is that the rents are kept high.”

Later, at the county board’s informational workshop on Oak Hill, John Carroll, the Marin superintendent of schools, said that Marin County Office of Education is 100% on board with the guarantor program.

“I’m absolutely supportive of this,” Carroll said Tuesday after a contentious exchange between him and board member Nancy McCarthy. “This is my decision to make, not the board’s.”

McCarthy has insisted the guarantor program needed more financial backing than just school and college districts. She suggested another plan could be to approach groups such as the Marin Community Foundation or the George Lucas Educational Foundation for additional funds, instead of asking school districts to backstop the development.

“None of the smart voices that oppose placing the financial risk of the Oak Hill affordable housing project on the backs of struggling local school districts is against affordable housing, as the promoters of this project try to peddle,” McCarthy said. “That tactic is a gimmick to evade hard questions about a rotten financial picture. Flailing schools can’t handle the risk.”

Marilyn Nemzer, president of the county board of education, disputed that notion.

“We must continue to find ways to recruit and keep the best teachers,” Nemzer said. “We are losing too many talented young educators because they can’t afford to live in Marin.”

The county education board is not expected to vote on the guarantor program because the authority for entering the program lies with the superintendent, and its members already agreed to support Oak Hill when they approved agreements to form the public financing authority in 2023, said Ken Lippi, senior deputy superintendent in the Marin County Office of Education.